Patrick Mannion

On October 4th, 1920, Irish-Canadian nationalist Katherine Hughes arrived in St. John’s, the capital and chief port of the Dominion of Newfoundland. Her objective was to establish a branch of the Self-Determination for Ireland League (SDIL) – a Canadian organization designed to win popular support for Irish independence during the peak of the Anglo-Irish War (1919-1921), and to connect those of Irish birth and descent overseas to a broader, transnational movement for Irish freedom. St. John’s was the final stop on Hughes’ British North American “Facts About Ireland” tour, which saw the establishment of dozens of SDIL branches in cities and towns across Canada. The League attracted thousands of members through 1920 and 1921, while countless more took part in its various meetings, lectures, rallies, and other events.[1]

Source: Library and Archives Canada, Mikan no. 4106511

In St. John’s, Hughes lectured to over one-thousand people at the Methodist College Hall on Long’s Hill. The event was a resounding success. Reporting to the leader of the nationalist movement in Ireland and President of the re-established Irish Republic, Éamon de Valera, she noted that: “Both the organizational meeting and the public meeting were splendid. The latter was the most representative I have had outside of Washington. […] Political leaders – the big men of the government – the leader of the opposition, judges, editors, merchants, financiers, clergy, and of course the rank and file [were present]. Many converts to the cause were made.” She concluded her report by stating that Newfoundlanders had “the warmest Irish hearts I have met outside of Ireland.[…] Poor Newfoundland, so much like Ireland in kind hearts, in predominance of Irish blood and accent, and has also been a land of exploitation of the many by the few.”[2]

Over the following weeks and months, the “Self-Determination for Ireland League of Newfoundland” thrived in St. John’s. It brought in speakers from mainland North America to lecture about Irish affairs, held well-attended meetings and social events, and published numerous articles in local newspapers that described the draconian actions of British police and armed forces in Ireland. Meanwhile, even though the League never publicly supported Ireland’s full separation from the British Empire, it drew vociferous opposition from what Newfoundland’s Governor, Sir Charles Alexander Harris, referred to as “loyal circles” – groups such as the Orange Order, whose members considered even moderate support for Irish nationalism to be inherently disloyal, or even treasonous.[3]

Self-Determination for Ireland League of Canada Application Card. American Irish Historical Society, Friends of Irish Freedom Papers, Box 2, Folder 4 (Office of the National Secretary Correspondence). (Photo by author).

As a historian of the Irish diaspora, what I find particularly fascinating about this widespread, dramatic – though short-lived – public engagement with the politics of Ireland is that hardly any of those who participated were born in, or had even visited, their ancestral homeland in Ireland. By the early-twentieth century, most Catholics of Irish descent in St. John’s were several generations removed from the “old land” – the city was home to just 127 Irish-born individuals in 1921.[4] As such, their understanding of “being Irish” was entirely constructed through the networks of the overseas diaspora. The surge in public Irish identity surrounding the SDIL brings up some of the key questions that unite historians of the Irish abroad: how was a sense of Irishness created, and how was this identity transmitted from generation to generation in overseas Irish communities? These questions guided my research in A Land of Dreams: Ethnicity, Nationalism, and the Irish in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Maine, 1880-1923. The book examines intergenerational ethnicity and nationalism in three medium-sized port cities on the prow of northeastern North America: St. John’s, Newfoundland, Halifax, Nova Scotia, and Portland, Maine. I argue, essentially, that a sense of “being Irish” did not evolve in isolation, but rather as a result of a complex interplay of local, regional, national, and transnational networks. The capacity for Irishness to remain a primary feature of a cohesive group identity did not necessarily wane generation by generation, but rather rose and fell through time, depending on circumstances in both old world and new.

These three cities, far removed from the continent’s Irish-nationalist hotbeds of New York City, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, or even Montreal, may seem like an unusual setting for a study of diasporic nationalism. Yet the unique nature of Irish settlement in each place sets up a fascinating examination of community and identity. Newfoundland is one of the oldest outposts of the Catholic diaspora. Migration and settlement took place primarily in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries as emigrants, almost all of whom were from within thirty miles of the port of Waterford, followed the networks of the migratory cod fishery and established themselves in St. John’s and in the fishing harbours of eastern Newfoundland. In the opening three decades of the nineteenth century, some 35,000 passengers were recorded – most arriving at St. John’s. In 1836, fully three-quarters of the city’s 15,000 inhabitants were Irish or of Irish descent, though this proportion declined through the remainder of the nineteenth century. By 1840, the migration was virtually complete – the vast waves of emigrants fleeing the Great Potato Famine bypassed Newfoundland. Irish settlement in Halifax was similar. Immigrants from the south and southeast arrived in the decades before the famine; many from Newfoundland as part of a“two-boat” migration. Although Irish migration to Halifax continued later than to St. John’s, both cities’ Irish communities were overwhelmingly native born by the 1880s, while Halifax was also home to more Protestants of Irish descent. The growth of the Irish community of Portland, by contrast, was a late-nineteenth century phenomenon. Migrants from the west of Ireland – particularly county Galway – settled in the city during and after the famine, with a subsequent wave of immigration in the 1880s. My comparative study, then, examines two well-established, overwhelmingly native-born Irish-Catholic communities within the British Empire, both well-integrated into each jurisdiction’s corridors of political and economic power, with a newer Irish-American community, comprising a much smaller minority in a predominantly Yankee-Protestant milieu.[5]

Unsurprisingly, echoing the findings of other diaspora historians, expressions of Irish nationalism in St. John’s and Halifax tended to be more moderate and constitutional; certainly less Anglo-phobic, than those in Portland. Even after the Easter Rising of 1916, clear, public support for a fully independent Irish Republic did not take hold in St. John’s or Halifax. Nevertheless, between 1880 and 1923, nationalist associations flourished in each port. The most influential of these, such as the Land League and Irish National League in the 1880s, the Friends of Irish Freedom (St. John’s and Portland) or the SDIL (St. John’s and Halifax) in the 1920s, were extensions of groups already established farther west. While a sense of Irish identity, of course, persisted in each community, it was these nationalist groups, through their public meetings, lectures, rallies, and articles submitted to local newspapers, that transformed latent ethnic consciousness into an active, public engagement with the politics of the old country. The intensity of these responses varied through time. My study revealed a surge in Irish identity at the beginning of the period – as many individuals of Irish birth and descent participated in the Land League and Charles Stewart Parnell’s movement for Irish Home Rule in the 1880s. This was followed by several decades where Irishness was seldom the basis for a strong, communal identity; while the climax of the narrative took place in 1920 and 1921, when a remarkable resurgence in expressions of Irish ethnicity took place in all three cities, even as the generational gap to the ancestral homeland was widest. While direct connections to Ireland were waning, expressions of Irish identity evolved in a thoroughly North American context.

An understanding and appreciation of “being Irish” was created in the households, schools, streets, and parishes of local communities, but for those of Irish descent, the connection to Ireland was strongly influenced by the extension of North American nationalist associations into each city. The study calls on us to consider how the networks of diaspora connected people and places, and how ethnicity not only evolved through time, but also diffused from place to place. That the third-, fourth-, and fifth-generation Irish of St. John’s and Halifax engaged with the politics of Ireland just as passionately as their first- and second- generation counterparts in Portland is a significant finding, demonstrating the tremendous persistence and spread – both temporal and spatial – of Irish identities in the global diaspora.

Patrick Mannion holds a PhD in History from the University of Toronto, and is currently is a per-course instructor in the Department of History at Memorial University of Newfoundland. His first book, A Land of Dreams: Ethnicity, Nationalism, and the Irish in Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and Maine, 1880-1923 was published by McGill-Queen’s University Press in July 2018. From 2016 to 2018, he was a SSHRC Postdoctoral Fellow at Boston College.

[1] The establishment and spread of the SDIL in Canada are well-covered in: Simon Jolivet, Le Vert et the Bleu: Identité Québécoise et Identité Irlandaise au Tournant du XXe Siècle (Montreal: La Presse de l’Université de Montréal, 2011); Padraig Ó Siadhail, Katherine Hughes: A Life and a Journey (Newcastle, Ontario: Penumbra Press, 2014); and Robert McLaughlin, Irish Canadian Conflict and the Struggle for Irish Independence, 1912-1925 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2013).

[2] Katherine Hughes to Éamon de Valera, 7 October 1920, University College Dublin Archives, Eamon de Valera Papers, P-150/995.

[3] Charles Alexander Harris to Viscount Milner, 8 May 1920, Colonial Office (CO) CO 194/298.

[4] Colonial Office, Census of Newfoundland and Labrador, 1921, Table I.

[5] On Irish immigration and settlement in these three cities, see: Matthew Jude Barker, The Irish of Portland, Maine: A History of the Forest City Hibernians (Charleston: The History Press, 2014); John J. Mannion, “Introduction,” in The Peopling of Newfoundland: Essays in Historical Geography, edited by John J. Mannion (St. John’s: ISER Press, 1977), 1-13; Terrence M. Punch, Irish Halifax: The Immigrant Generation, 1815-1859 (Halifax: International Education Centre, 1981).

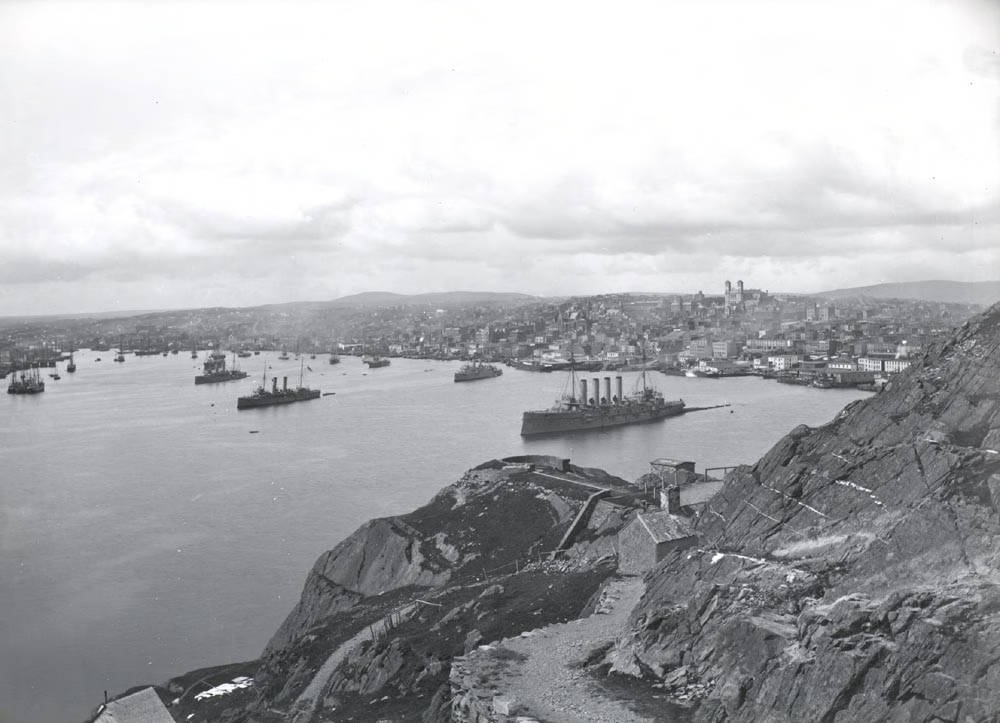

Featured Image: “View from the Battery looking east, with warships in the harbour, 1905,” Geography Collection of Historical Photographs of Newfoundland and Labrador (Coll-137), Archives and Special Collections, Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Latest Comments