Laura J. Smith

Buried within the papers of a World War One Chaplain is a remarkable record of the religious and financial engagement of Irish Catholic canal workers with the Roman Catholic Church in Upper Canada.[1] Meticulous notes penned by the Rev. John MacDonald, parish priest at St. John the Baptist in Perth, Upper Canada (1823-1837) detail his travels in 1831 along the Rideau canal between Merrickville in Montague Township and Jones’s Falls in South Crosby Township (see map). While the priest was at a canal site he celebrated mass; workers brought their children to be baptized; others were married or witnessed the marriages of friends and relations.

Map of the Rideau Canal (edited) courtesy of Ken Watson. http://www.rideau-info.com/canal/map-waterway.html.

MacDonald made careful record of the names, occupations (when they were canal workers), and the addresses (when they were settlers), of all those from whom he received money in 1831. He recorded the names of 623 canal workers, the majority of whom appear only once and had Irish surnames.[2] Cross-referenced with the Perth parish register for the same year, this record reveals details of canaller religious practice, what one labour historian has called a “demonstrated craving for spiritual guidance.”[3]

MacDonald’s records also situate the Irish Catholic workers within a colonial and religious world in which currency was increasingly important.[4] Though Alexander Macdonell, the Roman Catholic Bishop for the Diocese of Kingston, frequently complained of the adverse effects the poverty of the Irish had on the fortunes of his diocese, the Rev. MacDonald’s records make clear the financial significance of canallers to the priest’s ministry, and by extension, to the fortunes of the Roman Catholic Church in Upper Canada.[5]

Nineteenth-century canal workers expressed that “demonstrated craving” for religion in the construction of shanty chapels and temporary outdoor altars on canal lines throughout North America.[6] In Upper Canada, Bishop Macdonell noted that “virtually all” the workers on the Rideau were Roman Catholic and most were “extremely anxious” to build churches and secure the presence of a priest.[7] Demand for religion was such that suspended priests, men who had been dismissed from employment within the diocese for some wrong doing, could make a decent living “selling” sacraments in canal settlements.[8] On the Cornwall canal in 1836 workers refused to work on the feast day of St. Peter and St. Paul and attended mass instead.[9]

Roman Catholic workers on the Rideau were similarly mindful of their religious obligations. Canallers at Kingston Mills on the lower Rideau complained in September 1831 that priests from nearby Kingston had yet to give them the opportunity to complete their annual “Easter Duty,”[10] though the priests had been through to make collections.[11] This neglect was particularly frustrating as the previous spring they had begun construction on a chapel and had purchased a horse so that the Irish curate at Kingston, the Rev. Murtagh Lalor, could visit them more often. Bishop Macdonell had been lukewarm to their efforts at the time. He cautioned that settled Catholics in the surrounding townships had a prior claim on the priest’s time, and without a demonstrated financial commitment, not just to the support of a priest, but to the education of clergy in the Diocese of Kingston as a whole (for which he had received “not even a dollar from any Irishman”) he would not provide them with regular visits from a priest.[12]

Further upstream, the Rev. John MacDonald spent much of 1831 making extended and return visits to nine canal sites and encountered and ministered to canallers in regional towns such as Smith’s Falls and Perth. Some canal workers might have seen the priest once that year, while others saw him relatively often. For example MacDonald visited Chaffey’s Mills only once in 1831, while the labourers at Poonamalie (aka First Rapids) saw the priest on a day each in January, April, May, and June, three days in July, and a day each in August and October.

The priest’s visits were determined by demand, distance, ease of travel, and the season. Poonamalie was relatively proximate to Perth where MacDonald lived. Chaffey’s Mills was further downstream, but so too was Jones’s Falls where demand likely compelled the priest to make four visits that year. The season, both liturgical and temporal, also ordered MacDonald’s travels. During Lent and Advent he remained close to Perth and ministered only to settlers in the vicinity. During the late summer “sickly season” when malaria was rampant, he made very few trips to Rideau work sites.

Clerical income in the Diocese of Kingston in this period was frequently unreliable, inconsistent, and insufficient. Priests there had three sources of income: very occasional emergency help from Bishop Macdonell’s pocket; a perpetually decreasing share of the colonial government grant for Roman Catholic clergy and schoolmasters; and the unpredictable contributions of lay people.[13]

Poverty and a scarcity of cash in the colony as a whole, meant that the laity were frequently unable or unwilling to pay a tithe or for sacraments.[14] Clergy were instructed to accept penance in lieu of a fee. This was cold comfort for priests who often struggled to clothe and feed themselves. The lay people of Adjala Township, the Rev. Patrick O’Dwyer reported in 1841, were “lukewarm and indifferent,” to offering him “the common necessaries of life,” but did not spare [him] day or night whenever they wanted [his] assistance.”[15] In London, the Rev. Joseph Maria Burke could not charge full diocesan rate for sacraments and frequently went without breakfast. His predecessor had been unable to afford a winter coat.[16]

For his part, the Rev. John MacDonald’s records indicate that he often baptized children of parents who gave “nothing to the church” in return. In 1831 his annual share of the government grant was approximately £50. In comparison, the contributions and subscriptions he recorded in 1831 were more than double that allowance, and 67% or £82 came from canal workers on the Rideau. While Bishop Macdonell had been skeptical that Kingston Mills’ Catholic canallers could offer adequate support to a priest, it is clear that the Rev. John MacDonald’s canal ministry was a significant portion of his income.

The majority of the financial contributions MacDonald recorded on the Rideau were subscriptions: sums pledged (but not necessarily paid on that occasion) for the priest’s support probably on the occasion of a mass. For example on two visits to Esther Town in South Crosby in early January 1831, MacDonald recorded contributions from 97 canallers on the 8th totalling £2 3s 9d and from 79 canallers on the 11th totalling £8. The average contribution was 2 shillings 6 pence or a half-crown.[17] For an unskilled labourer it was at least a day’s wage, possibly more.[18]

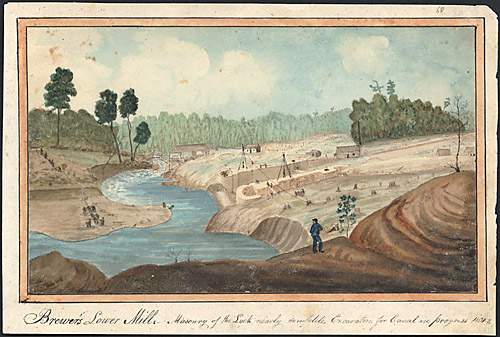

Brewer’s Lower Mill: Masonry of the Lock nearly completed, Excavation for the Canal in progress, 1831-2, Archives of Ontario, C 1-0-0-0-68, 1831.

MacDonald’s records reveal that participation in sacraments affirmed familial relationships and friendships on the Rideau. Canallers were godparents to each others’ children and stood as witness at each others’ weddings. When Patrick Kane married Nancy Foly at the Isthmus site in South Crosby in January 1831, the bride’s brothers Patrick and John stood as witnesses. When Ellen Wall married Daniel Warren at Poonamalie in September, in addition to two male relations of the bride, their wedding was witnessed by Richard Morris, a canaller for whose daughter Ellen was godmother.

About 22% of the events listed in the Perth sacramental register for 1831 can be conclusively linked to a canaller contribution in MacDonald’s financial records. Canallers were generous on the occasion of a sacrament, but more often paid the priest for his services at a later date. John Roche served as godfather to Bridget Reilly at Smith’s Falls on January 26, but did not make a 5 shilling payment to the priest until the 5th of June. Similarly Larance (sic) Lee, godfather to Patt Corrigan’s daughter Ellen baptized at Poonamalie on the 4th of April, gave the priest 2 shillings 6 pence on the 1st of August. While many canallers deferred payment, others simply did not pay at all. After the Warran-Wall wedding at Poonamalie in September, the priest waited in vain for payment from the bride’s brother, canaller Arthur Wall, as well as from the groom.[19]

Baptism and marriage events highlight the presence of women and children at a canal site. Women could account for up to a third of the population in a canal settlement and were a significant social and economic segment of the canal workforce, but a lack of evidence has meant their experiences have been marginalized in favour of analyses of the male culture and environment and the “worker families.”[20] MacDonald’s records provide some interesting evidence about the lives of canaller women.

Despite the male-dominated workplace within which canal children entered the world, there were sufficient numbers of women at Rideau worksites to ensure there was no shortage of godmothers. On the rare occasion a child baptized in 1831 had only one godparent (for nearly all had two) it was a godmother.

Women on the Rideau had access to cash and occasionally paid the priest for a sacrament event. In contrast, their settler counterparts never made payments to the priest on the occasion of a sacrament, but rather “gifted” (MacDonald’s word) the priest with food and clothing on an intermittent basis.

A canal mother’s payment at a baptism could be an indication that the child’s father was not present. Bridget McDory, “Mrs. Edward Flanagan,” gave MacDonald 2 shillings 6 pence at her daughter Mary’s baptism in Merricksville in June 1831. Mary’s baptism was notable also as her godmother, rather than her godfather as was common, contributed 5 shillings to the priest. The mother’s financial contribution could also be an indication of her particular endorsement of the rite. At the baptism of their daughter Bridget at Smith’s Falls in January 1831, Daniel Reilly and Ann McPhilips paid the priest 5 shillings and 2 shillings 6 pence respectively. Catharine Ferguson’s 5 shillings payment to the priest in June appears to have been an advance payment for the baptism of her daughter born ten days later and baptized shortly thereafter.

The children born on the Rideau in 1831 were baptized on average at about one month old. This was remarkably quick compared to the children of Roman Catholic settlers elsewhere in Upper Canada in this period.[21] This haste was indicative of not only the relative frequency of the priest’s visits that year, but of the importance accorded the rite by canal parents particularly amidst the precarious living conditions of the canal site.

Workers often travelled with newborns to meet the priest along the canal. James Daly brought his son William to the Mudlake site on May 26. William had been born the previous day in North Crosby, likely at the Narrows site. Daly must have had some foreknowledge of the priest’s schedule and perhaps knew that the priest would not return to the Narrows until August.

In other cases, canallers travelled to Perth to seek the priest’s services. In December, Michael Catin stationed at Poonamalie made the trip to Perth to have his one month old son baptized. So did Larance (sic) Contigan who went to Perth in August with his son who was baptized and his wife, Ann Downer, who became a convert to Catholicism.

A child’s baptism record occasionally noted that his or her father was deceased reminding us of the hazardous conditions within which canallers lived and worked. Yet the Rev. MacDonald presided over only one burial of a canal worker, meaning that most deceased Roman Catholic canallers were buried without the priest’s presence. Only one canal death was recorded in the Perth register. The death and burial of Thomas Kavanagh who had “departed this morning after midnight at Poonamalie at the age of about 35 years.” Kavanagh was buried in the Catholic burial ground at Perth. His body had been transported, perhaps by friends from the canal to Perth, a distance of at least 20 kilometres.

View of the Great Cataraqui Bay or South Entrance of the Rideau Canal with

Kingston in the distance – taken from the Mountain East of the Locks at Kingston Mills, 1830

Watercolour

Thomas Burrowes fonds

Reference Code: C 1-0-0-0-77

Archives of Ontario, I0002196

Amidst low pay, hazardous conditions, and erratic and insecure work, children were born and men and women married. Their participation in sacraments of baptism and matrimony enabled friends and relatives to cement their relationships and to build community on the Rideau Canal. The degree to which lay Roman Catholic religious practice in Upper Canada depended on a priest remains a subject of inquiry for my research, but I would argue that the Rev. MacDonald’s financial records suggest that for many canal workers, his service and presence was integral to their religious practice.

Laura J. Smith is a co-editor of Borealia and historical consultant. Her PhD dissertation completed in 2017 was on Irish Catholicism in Upper Canada. She can be found on Twitter @l4smith.

[1] Archives of Ontario (hereafter AO), Ewan MacDonald fonds, Collected Materials, 1762-1948: Papers Of Father John Macdonald (Series B-1) http://ao.minisisinc.com/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/ARCH_DESCRIPTIVE/DESCRIPTION_DET_REP/SISN%20517?SESSIONSEARCH. It is not clear if the Rev. Ewan MacDonald was related to the Rev. John MacDonald. The latter was an avid collector of the documents related to the colonial history of Glengarry County and in particular of the correspondence of Roman Catholic clergy from that area.

[2] French Canadians dominated the Rideau workforce. William Wylie estimates that 50% of the skilled workers and 75% of unskilled were French Canadian. William N.T. Wylie, “Poverty, Distress, and Disease: Labour and the Construction of the Rideau Canal, 1826-32,” Labour/Le Travailleur, 11 (Spring 1983) 9-12; Peter Way, Common Labour: workers and the digging of North American canals, 1780-1860 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993) 192.

[3] Way, 187-188.

[4] Brian Gettler’s forthcoming monograph Colonialism’s Currency: A Political History of First Nations Money-Use in Quebec and Ontario, 1820-1950 is one example.

[5] The financial contribution of the Irish laity to the global expansion of the Roman Catholic Church is an emerging area of inquiry. Sarah Roddy’s “Visible Divinity” project at the University of Manchester explores the massive monetary contribution of the Irish laity to the rapid infrastructural expansion of the Church in 19th century Ireland. My dissertation examines the financial dimensions of the establishment and growth of the Church in Upper Canada.

[6] In addition to Peter Way, see also Ruth Bleasdale’s “Class Conflict on the Canals of Upper Canada in the 1840s,” Labour/Le Travail vol.7 (Spring, 1981) 9-39 and Rough Work: Labourers on the Public Works of British North America and Canada, 1841-1882 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2018) Labour historians often emphasize the benefit of religion to the employer rather than to the worker. Highlighting cases in which priests operated as “double agents” ministering to workers while reporting on them to the employer.

[7] Archives of the Archdiocese of Kingston (hereafter AAK), Bishop Alexander Macdonell Letter Book (hereafter MLB) 1820-29, Bishop A. Macdonell to Bishop T. Weld, 6 May 1827.

[8] L. J. Smith, “Unsettled Settlers: Irish Catholics, Irish Catholicism, and British Loyalty in Upper Canada, 1819-1840” PhD thesis, University of Toronto, 2017. Archives of the Archdiocese of Toronto (hereafter ARCAT), Bishop A. Macdonell papers (hereafter M), AD07.02, Rev. Vinet to Bishop A. Macdonell, 3 August 1831; AAK, MLB 1820-29, Bishop A. Macdonell to Bishop J. Dubois, 26 January 1828.

[9] AO, Upper Canada Sundries, C-6890, J. Fitzgibbon to J. Joseph, 26 June 1836, pp. 91541-91543; J.K. Johnson, “Colonel James Fitzgibbon and the Suppression of Irish Riots in Upper Canada,” Ontario History LVIII, 1966, p. 152.

[10] Meeting one’s “Easter duty,” that is making confession and receiving the Eucharist once a year, was the minimum obligation for a practicing Roman Catholic in this period.

[11] AAK, MLB 1829-34, Bishop A. Macdonell to Rev. W.P. MacDonald, 28 September 1831.

[12] AAK, MLB 1829-34, Bishop A. Macdonell to Rev. M. Lalor, 31 March 1831; Bishop A. Macdonell to Rev. M. Lalor, 23 June 1831; Bishop A. Macdonell to Rev. W.P. MacDonald, 8 July 1831.

[13] An important, problematic, and controversial fund, the government grant for Roman Catholic clergy and schoolmasters began in 1827. It was a fixed amount of £750 and thus it decreased with each passing year as the Diocese grew and more clergy drew on the allocation. AAK, MLB 1829-34, “A distribution of the government allowance to Catholic clergymen and teachers in Upper Canada for the 6 months ending 31 December 1831” p. 206.

[14] Bishop Macdonell also frequently cited a cultural aversion to paying the tithe on the part of Irish Catholics.

[15] Being able to support a priest with the “common necessaries of life” was the basic commitment a Roman Catholic community made before the Diocese would send them a priest. ARCAT, M BB14.05, Rev. P. O’Dwyer to Bishop R. Gaulin, 6 February 1841.

[16] ARCAT, M AB05.04, Rev. J.M Burke to Bishop R. Gaulin, 19 June 1837; AB31.07, Rev. W.P. McDonagh to Bishop A. Macdonell, 8 October 1837; AB10.01, Rev. L. Dempsey to Bishop A. Macdonell, 20 November 1832.

[17] In a cash-scarce economy, and in low-paying work place it is very likely few canallers had their subscribed amounts on hand. Ian Radforth found that shantymen occasionally hosted missionaries who collected subscriptions which were deducted from the workers’ end of season pay. Ian Radforth, Bushworkers and Bosses: Logging in Northern Ontario, 1900-1980 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1987).

[18] Skilled workers could make between 5-7 shillings a day, an average labourer’s salary was 2-3 shillings a day. Some contractors paid less but offered room and board. Wages were also dependent on economic and seasonal factors. Wylie, 14.

[19] AO, Ewan MacDonald fonds, Correspondence of Rev. John MacDonald, Rev. J. MacDonald to Arthur Wall, 3 September 1831.

[20] Way, 168-169, 171; Bleasdale, “Class Conflict,” 33. The Rev. MacDonald did not distinguish between male and females on the canal works, both were annotated with the “canaller” mark in his notes.

[21] In Lanark and Ramsay Townships on the northern edge of the Rev. MacDonald’s parish, the average age at baptism was 3-4 months. Elsewhere in the province, the average age at Assumption parish in what is now Windsor was 115 days and in the Dundas mission in the late 1820s it was 9-10 months.

Featured Image: Thomas Burrowes, View on the Cataraqui Creek, Brewer’s Upper Mills in the Distance, 1830. Wikimedia Commons, public domain.

Latest Comments