[This is the sixth essay of the Borealia series on Cartography and Empire–on the many ways maps were employed in the contested imperial spaces of early modern North America.]

Alan MacEachern

The following post may not suit a scholarly discussion on cartography and empire. You’ve been warned. Here be dragons, and all that.

This summer, I curated “Missing the Island,” an exhibit at the Confederation Centre of the Arts in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. It tells of how PEI, its sandstone base worn away by the surrounding waters over the millennia, at some point broke free and now periodically floats around the North Atlantic, until the tides carry it back to the Gulf of St. Lawrence. It was this peripateticism that led Mi’kmaq passengers to name the isle Epekwitk, or “cradled on the waves.” The exhibit documents the history of how mapmakers and illustrators have attempted to capture the Island’s absence visually, while others, perhaps, have been utterly unaware of its existence.

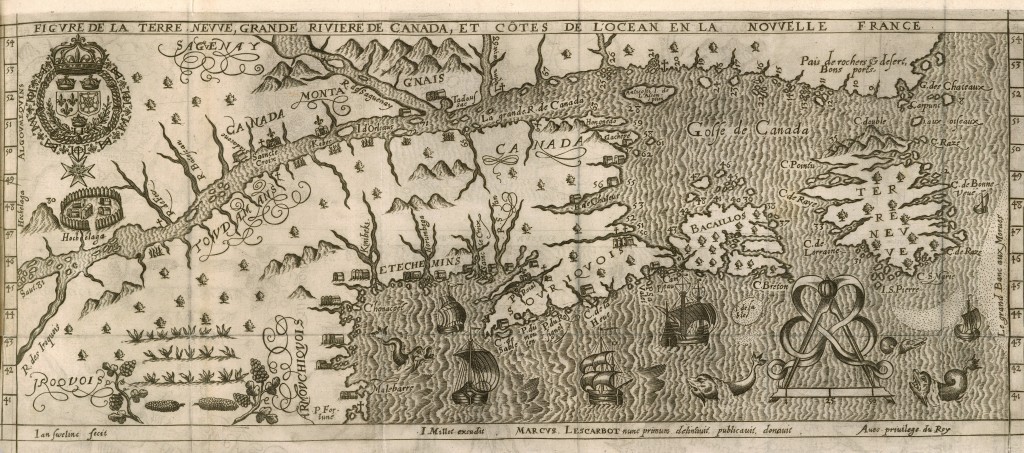

Marc Lescarbot, “Figure de la Terre Neuve, Grande Rivière de Canada, et côtes de l’Océan en la Nouvelle France,” 1609, courtesy of University of Western Ontario Libraries.

The exhibit utilizes images from three eras: the 1500s-1600s, the mid-1800s to early-1900s, and today. The first of these will be of primary interest to Borealia readers. Jacques Cartier described Prince Edward Island as what has usually been translated as “the fairest land ‘tis possible to see” (who knew that “’tis” was a standard 16th century French usage?) but as a considerable number of maps from this era make clear, PEI was not always possible to see. While PEI’s mobility gave the Mi’kmaq a final, short-lived solitude, it also hampered the colony’s development within the French and then British empires. For example, British property law was unprepared for itinerant land masses, so unscrupulous lawyers took advantage. This was the era of “absentee land” lords.

John Arrowsmith, “British North America,” 1832, courtesy of University of Western Ontario Libraries.

The 1802 map of British North America by famed English cartographer John Arrowsmith is unusual, in that by this era most every map shows Prince Edward Island’s existence. Either PEI was not travelling so much, or else illustrators happened to catch it while it was in the Gulf, or they were illustrating it as if it was there. We don’t know which: more research (and therefore more funding) is needed. In any case, even after joining Canada in 1873, PEI periodically left it, and this nomadic nature continued to have profound effects on the Island’s economic and social development. For example, geographical migration encouraged demographic outmigration, and Islanders later embraced the tourism industry because they had so often been tourists themselves. It was hoped that the construction of the Confederation Bridge in 1997 would tether the Island to Canada once and for all, but still it drifts.

You get the idea.

Hendrick Doncker, “Pas-Caert van Terra Nova, Nova Francia, Nieuw-England en de groote Rivier van Canada,” 1660, 093:462 M, courtesy of the Huntington Library, San Marino, California.

I developed this exhibit because it was fun. Fun to tell a counterhistory of my home province. Fun to pore through online map databases, like mugshot books, for images in which something was awry. Fun, too, to document PEI’s membership in the fraternity of small islands that share this affliction of being left off maps. There is a Reddit group devoted to examples of New Zealand’s habitual exclusion, for example, and earlier this year Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern and comedian Rhys Darby launched a campaign to put their country back on the map.[1] The Maltese are also perennially overlooked, I am told. And more locally, I would estimate that historically Cape Breton has been five times as invisible as PEI. (And if the Cape Breton University Art Gallery is looking for an exhibit for 2019….)

Alain Manesson-Mallet, “Canada ou Nouvelle France,” 1683.

I also hoped the exhibit would encourage viewers to think about maps and the places they depict. We too often think of maps today, like photographs, as unmediated replications of reality – “surrogates for firsthand seeing,” in Joan Schwartz’ elegant phrasing.[2] We think, sure, some early ones were inaccurate, but all those bugs have been worked out, right? The fact that the “Missing the Island” exhibit includes so many examples from the 21st century reminds us that the translation from reality to representation always necessarily involves simplification – and so, still sometimes involves human error. The exhibit might also make viewers contemplate their own assumptions about what makes some places count, and not others. Two separate people pointed out to me that many of the early mapmakers who omitted Prince Edward Island nevertheless included Anticosti Island. Imagine, including that little rock but not PEI! But Anticosti is actually a little larger than PEI, and was perhaps more strategically important (and harder to miss) because of its location at the outlet of the St. Lawrence River. It is only as a colony and then a province that Prince Edward Island has become bigger than Anticosti in our minds.

Samuel de Champlain, Les Voyages, 1613, courtesy of University of Western Ontario Libraries.

But the main reason I launched this exhibit was just to change the narrative. Nowadays, when some idiot from away forgets to put PEI on a map, there is typically a human interest story in the news, with an Islander pointing to the spot on the map where the Island should be. They are clearly hurt that their home has been overlooked – and that by extension they have been too.[3] It is natural that a small place fight to maintain its position in the world, that it make sure it is not forgotten. But such a reaction is, well, reactionary. I wanted to take things in a more active, positive direction, to tell a story in which the Island itself is active, is mobile, and that is why some mapmakers miss it. I wanted to give Prince Edward Islanders a magnified vision of their home. If, that is, a community that possesses all the advantages of being a province of Canada while having a population smaller than Sudbury needs it.

From W.R. Norris, “Norris’ Cyclopaedic Map of the United States of America,” 1885, courtesy of David Rumsey Map Collection, https://goo.gl/X97BaU.

Alan MacEachern teaches & researches Canadian history, with an emphasis on environmental & climate history. He is Professor of History at the University of Western Ontario, and was formerly Director of NiCHE. He can be found on Twitter @alanmaceachern.

[1] See “Maps Without NZ,” Reddit.com, and “Jacinda Ardern Asks Why New Zealand Is Left Off World Maps in New Tourism Campaign,” The Guardian, 2 May 2018.

[2] Joan M. Schwartz, “Photographic Reflections: Nature, Landscape, and Environment,” Environmental History 12 (October 2007), 966-93.

[3] Having written this, I realized I should have evidence. It was easy to find: “’Come On, It’s Part of Canada’: Islanders Upset PEI Left Off Maps,” CBC News, 7 March 2017.

Featured Image: From “Carte angloise de la Baye de Hudson ou la compagnie apellee Hudson Bay fait son commerce,” 1719, courtesy of Edward E. Ayer Digital Collection (Newberry Library), https://goo.gl/sjWFkk.

The island long ago fought back. See Atlas of Province of Prince Edward Island, Canada, and the world (Toronto : Cummins Map Co., [1925?])