Laura J. Smith

In the summer of 1824 the British Colonial Office instructed the Upper Canadian government to give a soon-to-arrive Irish emigrant named John Dundon a “gratuitous” land grant of 200 acres and provisions for a year.[1] Such assistance was not unusual. Assisted emigration programs targeting disbanded soldiers, dispossessed peasants, and unemployed craftsmen had already contributed substantially to the Upper Canadian settler population. But why did this particular emigrant warrant individual attention? A second letter sent a few weeks later went further: “John Dundon rendered some important services to the Irish government as an informer and… has been provided for as a settler.” Dundon was to be sent to the Lake Simcoe region, the letter instructed, for “the vicinity of the other settlers would be hardly safe for him.”[2]

John Dundon was a notorious “Captain Rock”; a leader within the Rockites, a secret agrarian protest group active in the Blackwater region of North County Cork in the mid-1820s. [3] Like similar Irish groups of the period, the Rockites agitated for social and economic change and particularly for the reform of access to and ownership of land. They targeted, usually through vigilante-style violence, all those who blocked the peasantry’s access to land. Dundon’s arrest and confession, which identified 50 local Rockites, and locations of substantial caches of arms, was a coup for beleaguered magistrates tasked with subduing the increasingly violent Rockites. Dundon’s information proved valuable, and consequently officials lobbied for a provision that might double as protection for Dundon and his family who it was noted, could no longer remain safely in Ireland.[4]

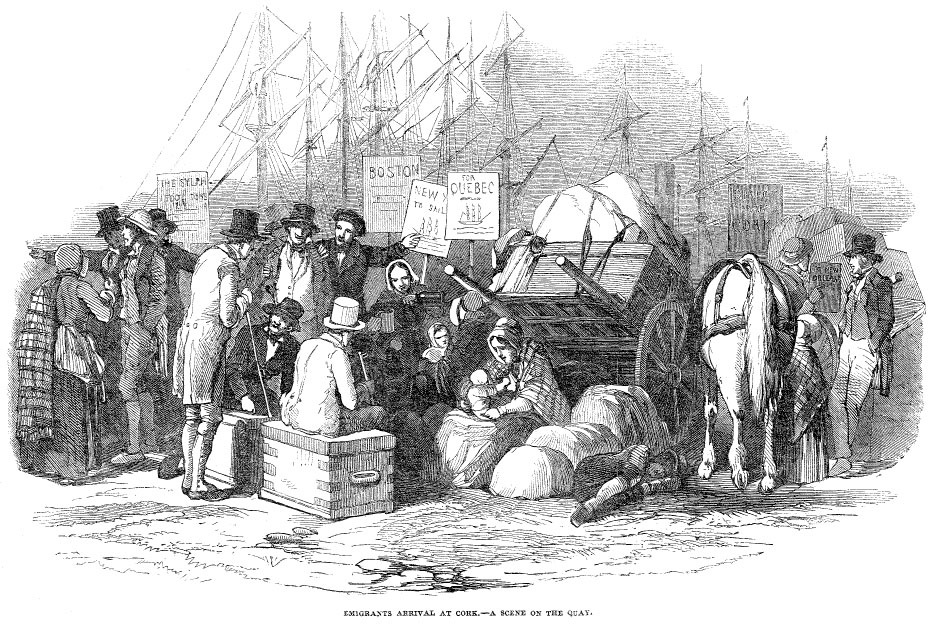

Emigrants Arrival at Cork–A Scene on the Quay. Illustrated London News, May 10, 1851. Public Domain via Steve Taylor at https://viewsofthefamine.wordpress.com

That Dundon was directed to Upper Canada is not surprising. The previous summer the British government had conveyed nearly 600 mostly Irish Catholics, the “other settlers” from the Blackwater to eastern Upper Canada under similar, but slightly less generous assistance terms.[5] Dubbed the “Peter Robinson emigrants” after the Upper Canadian who superintended their migration, they were the first of two groups of Irish Catholics sent to Upper Canada from the region.[6] Their assistance program was premised on contemporary ideas about the removal of “surplus” populations to ameliorate agrarian discontent and free land for modernization. The Blackwater region was targeted specifically because of the escalation of Rockite violence, and the intense lobbying of local landlords. Land use was changing, landholders argued, and the peasant farmer was obsolete. Such men, who in Ireland had rented a few acres for basic subsistence, were better settled in Canada where they could “cultivate the waste lands…and be useful members of society.” Left in Ireland, they were likely to turn into “bad subjects” who devoted their “time to Captain Rock and his associates.”[7]

There is no explicit evidence that any of the 1823 emigrants were Rockites, or that the assisted emigration scheme that year was used to transport troublemakers. Irish sources are inconclusive, and it appears more probable that participants, particularly a group of Irish Palatines, emigrated out of fear rather than complicity with the Rockites.[8] Though he insisted he chose only “paupers” who had agricultural experience, and thus had a chance to do well in Upper Canada, Peter Robinson was vague on the extent to which his emigrants could be implicated in the violence. Arguing that even the most “fiery” Irish male no matter his “former conduct,” could be tamed with a fresh start in Upper Canada, Robinson admitted that he had allowed local magistrates to select from the list of willing migrants those, “they [were] most desirous to get rid of.”[9] Such sentiments reflect an elitist view of the disposition toward anti-social behaviour that was both natural to the Irish character and nurtured by the Irish environment. For imperial officials explicit participation in secret societies was largely irrelevant for the state of Irish rural society made every inherently disorderly Irish peasant a potential Rockite.

The assisted emigrants were met with similar sentiments in Upper Canada, where perceptions and stereotypes that Irish Catholics were violent or easily provoked into violence persisted. Certainly their new neighbours needed little proof that the 1823 emigrants were Rockites or carried politically problematic baggage. The assistance the Irish had received was seen locally as underserved, Peter Robinson reported; the Irish, it was said, “had done nothing to entitle themselves to any bounty from the government, further than keeping their own country disturbed.”[10]

Irish Emigrants Leaving Home–The Priest’s Blessing (1851) New York Public Library Digital Collections.

When a few members of the 1823 group were implicated in a tavern riot in the spring of 1824, locals saw confirmation that the violence of rural Ireland had been transplanted in their midst. Area officials immediately solicited military intervention certain that an insurrection was afoot. Drawing on tropes familiar to anyone who had read accounts of rural agitation in Ireland, the Montreal Herald depicted the emigrants as mindlessly violent, defiant of all authority, and opposed to the natural order of settlement life. Their violence was indicative, the paper implied, of those “permanent political feelings incident to a great proportion of Irish Emigrants.”[11] Despite absolution from a colonial investigator following the tavern riot, and clear evidence of settlement success, his fellow Blackwater emigrants continued to be plagued by the stigma of violence and questionable politics decades after their initial arrival.[12]

It is little wonder then that John Dundon was to be directed away from eastern Upper Canada and the emigrants who were under such close scrutiny and stigma. Engaged in a potentially large-scale and long-term project of assisted migration and settlement of Irish Catholics to Upper Canada, the Colonial Office wished to avoid further scrutiny of the goals of its colonial emigration policy, particularly accusations that it was prioritizing the displacement of Irish violence over the safety of Upper Canada. The settlement of John Dundon, an actual confessed agrarian rebel, had to be done carefully and quietly. It appears they were successful. It is not clear if Dundon claimed his reward in Upper Canada.[13] Land records for the colony offer a few misspelled, but inconclusive possibilities in Tiny, Vespra, and Mariposa Townships.[14] Of course it is possible he changed his name, or continued to the United States, but regardless John Dundon, it would seem, slipped into obscurity.

Considered together, the stories of John Dundon and the 1823 emigrants reveal the extent to which scrutiny and stigma of recent migrants, particularly those from disturbed regions and for whom state assistance is given, is nothing new. The state-sponsored migration and settlement of the 1823 emigrants sparked discussions about security, funding, reception and cultural integration, issues that remain important in 2016.

Laura J. Smith is a PhD Candidate in the department of history at the University of Toronto. Her forthcoming dissertation is entitled: “Unsettled Settlers: Irish Catholics and Irish Catholicism on the British North American settlement frontier, 1820-1840.” She can be found on Twitter @l4smith.

[1] Much of this post is drawn from the forthcoming: Laura J. Smith, “The Ballygiblins: British emigration policy, Irish violence, and immigrant reception in Upper Canada,” Ontario History, Vol. CVIII No. 1, Spring 2016.

[2] Archives of Ontario, Upper Canada Sundries, C-4613, p. 35320, Peter Robinson to Major G. Hillier, 12 June 1824; p. 35793, Peter Robinson to Major G. Hillier, 1 August 1824; Archives of Ontario, Peter Robinson Fonds, MS12, Reel 1, Major G. Hillier to Peter Robinson, 24 October 1824; Peter Robinson to Robert Wilmot Horton, 7 December 1824.

[3] James S. Donnelly, Captain Rock: The Irish Agrarian Rebellion of 1821-1824 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2009) is the definitive history of the Rockite rebellion.

[4] National Archives of Ireland, State of the Country Papers, 2514/24, Finch to Arbuthnot, 19 July 1823.

[5] Male assisted emigrants over 18 were given 70 acres of land in the Bathurst District. A provision for the an additional 30 acres was to be made once the emigrants proved themselves to be “industrious and prudent.”

[6] The second assisted emigration in 1825 was larger, and sent approximately 2000 emigrants to the area around what is now known as Peterborough.

[7] Archives of Ontario, Peter Robinson fonds, MS 12, Reel 1, Kingston to Robinson, 19 December 1824.

[8] A search of the State of the Country Papers at the National Archives of Ireland revealed no explicit participation in Rockite violence on the part of the selected 1823 emigrants. For more on Irish Palatines see, Carolyn A. Heald, The Irish Palatines in Ontario: Religion, Ethnicity, and Rural Migration, (Gananoque: Langdale Press, 1994).

[9] Library and Archives Canada, Colonial Office 384/12 f. 21, Peter Robinson to Robert Wilmot Horton, 9 June 1823; Archives of Ontario, Peter Robinson fonds, MS 12, Reel 1, undated report by Peter Robinson to Lord Bathurst.

[10] Reports from the Select Committee on Emigration, (Great Britain: Parliament, House of Commons, Select Committee on Emigration from United Kingdom, 1826) p. 332.

[11] Montreal Herald, 5, 12, and 15 May 1824.

[12] Thirteen years later, when news of the aborted Upper Canadian rebellion reached London, observers there immediately assumed, entirely erroneously, that the 1823 emigrants would be implicated in the affair. See Robert Wilmot Horton, Ireland and Canada, supported by Local evidence, (London, 1839) p. 76-78, https://archive.org/details/cihm_21752. Perhaps anticipating questions about their loyalty, the Irish Catholics in the region sent a loyalty address to the Lieutenant Governor. See, Colin Read and Ronald J. Stagg ed., The Rebellion in Upper Canada: A Collection of Documents (Ottawa: Champlain Society, 1988) 263-265.

[13] Archives of Ontario, Peter Robinson fonds, MS 12, Reel 1, Major G. Hillier to Peter Robinson, 24 October 1824 indicated that Dundon had yet to arrive but was expected imminently.

[14] Archives of Ontario, Ontario Land Records Index, 1789-1920.

Featured Image: Irish White Boys, from George Lillie Craik and C. MacFarlane, The Pictorial History of England: Being a History of the People as well as a History of the Kingdom, Vol. 5 (London: Charles Knight, 1849), 79. Public Domain via Google Books.

Latest Comments