Leah Grandy

Future historians are facing a crisis in a skill set that has not been a significant issue in the past. As the teaching of cursive writing has been eliminated or greatly diminished from North American elementary school curriculums, we are seeing the arrival of university students to arts programmes unable to read written primary documents. Current undergrad students (yes, they are here now!) possess little of the experience with cursive writing needed for interpreting many historical manuscripts; they also are facing struggles in the classroom reading professor’s notes and completing written exams in a timely fashion.

Image: Notation on a declaration for letter of Marque exhibiting a writer’s individual style, abbreviations, and the long “ss” (“commissions”, not “commiffions”) which can be problematic to those unfamiliar with cursive writing.

The urgency of this issue was first noticed during outreach to get undergrad students involved with UNB Libraries’ The Loyalist Collection and in the training of student assistants for a transcription project involving New Brunswick’s County Courts of General Quarter Sessions of the Peace which are situated in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. The Loyalist Collection can be intimidating to novice researchers although the content is quite “recent” by historical standards. The Collection mainly covers the years 1750 to 1850 and comprises material from across the Atlantic world, including a large amount of colonial Canadian content. It has been taken for granted in the past that new historians working in this period would be able to learn to interpret documents from this period on their own, but it is becoming more apparent that some guidance should be provided.

Universities offering degrees in history and related disciplines must proactively combat lack of understanding of cursive writing by providing basic instruction in palaeography (the art of reading and deciphering historic handwriting and manuscripts) to students. By offering an introduction to historical writing, some of the fear (or indeed abject terror) surrounding tackling primary, handwritten documents is reduced or removed. Whereas previously palaeography instruction was only extended to Medieval and perhaps Early Modern history students, now guidance will be needed for later centuries and Canadianists as well.

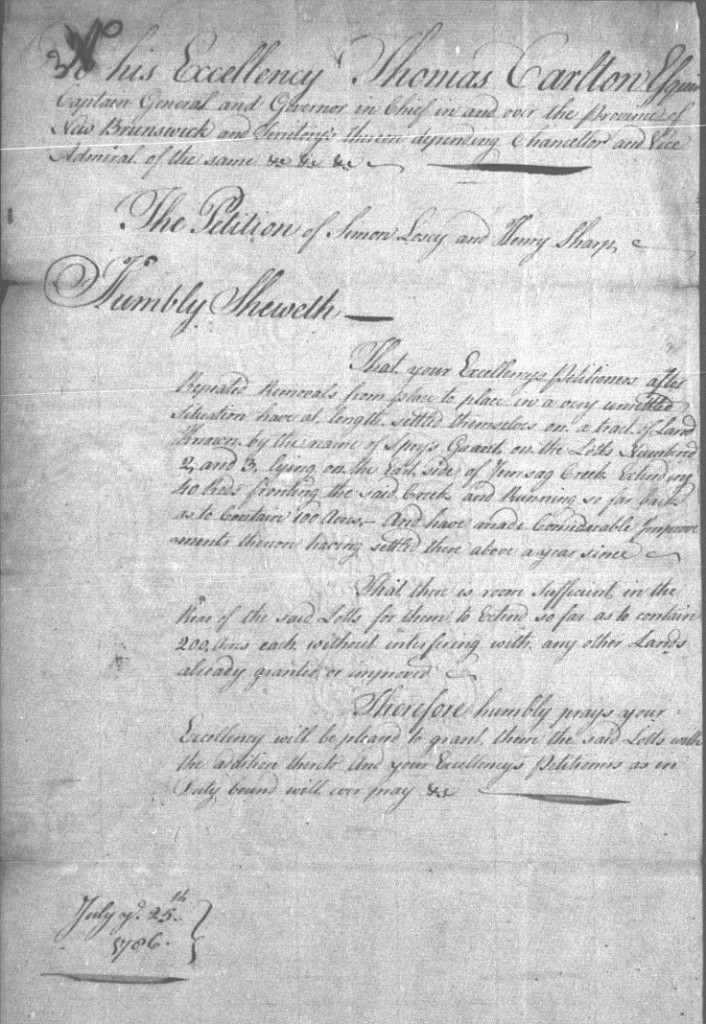

Image: The titles and headings are emphasized in this New Brunswick land petition document by an alternate type of hand, while the majority of writing is in copperplate hand.

“Introduction to Palaeography”, a two-part pilot session focusing on writing in eighteenth and nineteenth century North America and Britain, was initiated at UNB Libraries (Fredericton, New Brunswick) in Winter Term 2016 and provided useful insights into the needs of students and instructors. The first part of the session consisted of a lecture combining an orientation to palaeography and transcription. Topics covered included writing materials, hands, and particular tricks for dealing with historical scripts. The introduction was followed by practical tips and examples of these techniques in action such as matching identifiable letters to unknown letters and cross referencing with another document. The second session involved a hands-on analysis of a document for which a background reading had been given previously. The document was examined and transcribed individually or in small groups, and then the group reconvened for discussion and reflection.

Image: Practice document used for “Introduction to Palaeography” session, a description of slaves in Barbados by Joseph Senhouse, Memoirs, volume 3, 1779.

The approach was taken to the instruction that skill at interpretation of writing is gained through experience. It is of great benefit, however, to understand the subject area of the document and that writing varies by place, time, and individual. Indeed, palaeography can be utilized as an identifier for many document details if they are unavailable. A suggested series of major questions to be posed when approaching a new document included:

- Who created this document?

- Where and when was it created?

- Why was it created?

- What material were used in its creation?

The objective in offering an introduction to historical cursive writing was that students will be more apt to dive into primary sources for their research projects, such as those held within The Loyalist Collection, when they have already gotten their “feet wet”.

Image: Record of unusual shipwreck deaths under burials lists in 1796 highlighted by box, St. John’s, Cornwallis, Nova Scotia. This type of context would not be evident in a transcription of the document.

Without intervention, many students will only be able to read transcribed or typescript primary documents, and would lose out on context and detail, such as the emotion of anger expressed in the style of the writer’s script or later notations and edits which could be germane to the dating, creation, and purpose of the document. With the loss of ability to read written documents in their original form, future historians will be unable to unearth important nuances which shape the interpretation of early Canadian history.

We have posted a how-to essay on palaeography over at The Atlantic Loyalist Connections blog.

And here are some other online palaeography resources. While these mainly pertain to Medieval and Early Modern documents, the principles still apply to later periods:

Institute of Historical Research, University of London

The National Archives (London)

Cambridge University online course

Brigham Young University Script Tutorial

Leah Grandy holds a PhD in history and is the Microforms Assistant working with The Loyalist Collection at the Harriet Irving Library, University of New Brunswick. Her research interests are varied and currently include colonial naming practices, Maritime regional history, and instruction in palaeograpy. She is an editor of the new blog Atlantic Loyalist Connections.

To this excellent post I would like to add the need to do critical analysis of the documents as material objects. How does the historian figure out if the document is an original or a copy? if there have been insertions or excisions? where the paper came from? (there’s historical material there!) and other points that only study of the material object can reveal. I did a guide for historical editors of Champlain Society editions which is on our web site, and dialogue with a scholar friend currently editing a CS text shows how much this kind of skill is needed! See http://www.champlainsociety.ca/the-champlain-society-guidelines-for-editing-canadian-historical-texts/cs-editorialguidelines-complete/

Thank you very much for your response and for bringing up other elements of documentary analysis which need to be explored with students. I completely agree that examining the material circumstances of a document’s creation adds to historical knowledge and insight.

Actually, the skills I was referring to are generally taught (when they are taught at all, that is!) under the heading of “Bibliography.” I learned them because I have a PhD in English, not history, and have been pressuring historian friends to learn them ever since. Classic example: Historians quote Holinshed’s History as if it were a single authoritative text, whereas, as Randy McLeod demonstrated some years ago, there were hundreds of changes in press that differentiate one copy from another! And there are many modern examples as well. Bibliographers (a dull title, but the only one available) have dozens of horror stories to tell about other cases.

I have received wonderful support and interest from the English Departments, as it is a skill they certainly value.

Dr. Grandy, I appreciated this thoughtful post. As an archivist who works with colonial and early American manuscripts, I often encounter vestiges of English secretary hand in my transcription work. As a museum educator, I’m finding more and more that my students aren’t prepared to handle the nineteenth-century documents either. You might be interested to see how we have intervened here at the Morristown National Historical Park, Morristown, NJ, USA. We do a lot of document analysis training with youth via programming and our collections blogs. You might really like our Archival Ambassadors initiative: http://primarysourceseminar.blogspot.com/search/label/Archival%20Ambassadors

What a fantastic program! Thank you for bringing it to my attention. Early intervention would be ideal for this issue. We actually hold copies of the Lidgerwood Collection from Morristown National Historic Park in our Loyalist Collection.